-

Talent Buying and the Art of Marking Up Artist Contracts

For those of you that are handling talent buying for your event or festival, it’s important to understand the various steps in the process. This will help ensure you are both protecting yourself and creating a supportive environment for the artist to perform.

In this article, we will break it down into the following sections:- Researching artists that may fit your budget and your event or festival’s entertainment goals

- Contacting the various booking agencies tied to your wish list of artists and finding out general price ranges and availability

- Making a formal offer to the agency

- Reviewing and marking up the agency / artist contract

- Receiving a fully executed contract back from the agency

This is the goal – to have your top artist playing for plenty of happy fans

Artist Research

First, you’ll want to have a good understanding of what sort of talent to seek based on your event’s budget and target demographics. Due to the myriad of booking agencies, there isn’t a one-stop-shop that simply lists how much every popular performer will cost you. And even if there was, the price can often be fluid based on their circumstance and desire to play.

A good source to do some research on how much artists may cost is Pollstar Pro (Celebrity Access is another). For an annual fee, you will have access to their vast databases which will provide the following information:

A good source to do some research on how much artists may cost is Pollstar Pro (Celebrity Access is another). For an annual fee, you will have access to their vast databases which will provide the following information:- Previous concerts / festivals played dating back years – see screen shot to the right as an example from Pollstar Pro

- Average ticket sales per performance

- Average gross revenue per performance

- Their booking agent’s contact information

You’ll want to utilize this to see when the last time they played your market was, what venue they played in, and how much they sold in tickets / made in revenue. Note that the revenue is before any expenses; it isn’t going to be the net income the band took home, but it’ll be a good idea of what you may have to offer in order to catch their interest. For example, if an arena level artist routinely makes over $1,000,000 at their shows, you won’t want to make an offer of $200,000; that would be way too low. However, you likely won’t have to make an offer over $1,500,000 either – they are probably taking home between $500,000 and $750,000 so perhaps an offer in that range brings you good value and them a good payday. A lot of variables will come into play during this process, and if they don’t feel like playing for, let’s say, less than $3,000,000 – and have no reason to play otherwise – you don’t really have much room to negotiate.Next, you’ll want to create your wish list with the understanding that even if a band is available, and they’re in your budget, it may still not end up happening due to other circumstances or a change in touring strategy for the band. Have multiple options for your headliners, middle tier, and opening acts.

In an ideal world, you’ll have at least nine to twelve months of lead time to properly lock in your artists – larger, nationally touring acts are especially booked up far in advance. Regional and local acts can be booked with less lead time.

Reaching Out To the Agencies

With your wishlist in hand, it’s time to start reaching out to the agencies (for smaller bands that represent themselves, you’ll be reaching out to their primary point of contact, which can often be found on their website). One way is to email or call the agent directly and ask what the general price range and availability is for the artist(s) you’re looking at. More often than not they will give you a range, so you at least know where the market is on that particular artist before you have to make an offer. If you feel like the range is too high based on your research, you’re always free to offer something lower and most of the time the agent will at least take the offer to the artist. If it’s too low, the artist will either counter or simply pass altogether. The agent will normally be upfront and honest with you on what’s not even worth taking to the artist, money-wise.

Another good talent buying strategy is to see how many artists on one agency’s roster you would be happy with at your event or festival, and work together with the agent to stay within your talent budget but land the artists desired. This sort of strategy works best with the larger agencies, like William Morris Endeavor, Creative Artists Agency, Windish Agency, APA, and Paradigm. The agent will be compelled to work out deals that may not be done if you were just utilizing them for one of their artists, and it could grow into a mutually beneficial long term business partnership down the road.

As you make your calls and build up your talent availability grid, you’ll be able to show who is available, for about what price, and any other key details that may or may not make the difference in making a formal offer. For example, one artist may be willing to play but would require you to not publicly announce their involvement in your event or festival until after they play a nearby city. This could negatively impact your marketing campaigns, so it’s something to consider.Making a Formal Offer

You’ve whittled down the available artists within your event or festival’s budget to your dream lineup and you are ready to proceed. Now it’s time to make your offer. But please note:

Any offer you make to an agency may be considered legally binding.

Be sure that you’re financially ready when you make the offer.

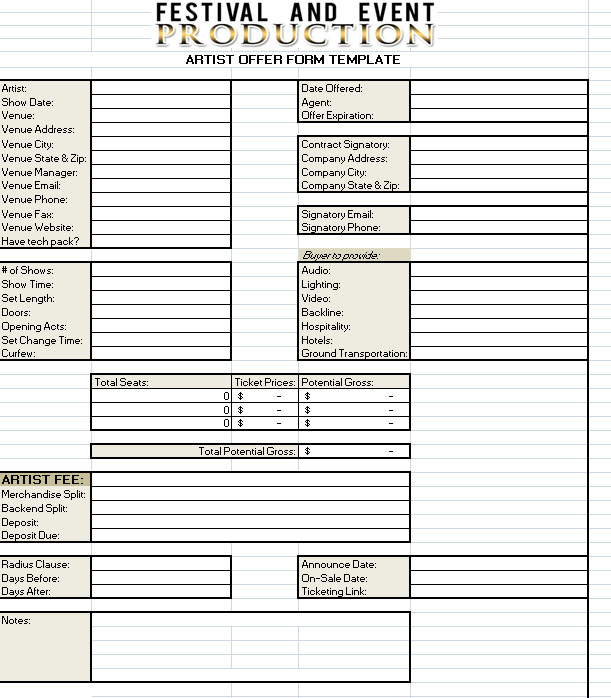

If the agency doesn’t have a required method (i.e., filling out their online offer forms), below is an example of one you can customize. Here is where you’ll also want to state your terms for other elements that often become part of your talent expenses, so when the agency creates the master contract, these terms are already in there.

You will want to base these terms on what the artist is asking for in their technical and hospitality riders; if you aren’t 100% sure on what to look out for in these documents, be sure to include other key stakeholders in these conversations, such as your Production Manager and/or Stage Managers along with your Hospitality Manager as they will be able to help you understand why the band is asking for what, and what’s feasible to provide.

Download this as an Excel spreadsheet

In the offer form, you’ll want to make sure you cover these elements:- Radius Clause – how far away are you willing to have the artist play other public performances, and how much time is acceptable before your event or festival as well as after it?

For example, if you are booking a headlining act in Austin, a radius clause of 300 miles will ensure that the artist will not book any performances in Dallas, Fort Worth, San Antonio, or Houston – all major markets that could significantly affect your attendance, especially for a festival.

Often you’ll want a minimum of 90 to 120 days before to ensure enough time has passed to build up demand again, but for larger acts this may need to be set as far back as one year. For smaller acts, especially local ones that rely on steady income from local gigs, you’ll want to reduce this to 30 days or less depending on what sort of impact those gigs may have on your event.

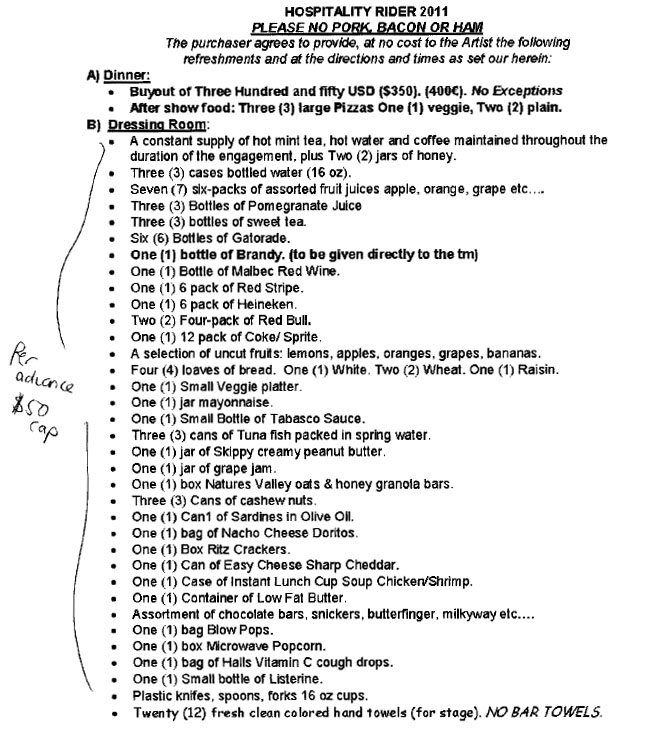

As for after the event, you’ll also want some buffer time so people aren’t tempted to buy tickets to that event instead of yours, but often the time frame doesn’t need to be as long; 30 to 60 days is pretty standard. - Hospitality Cap – this is a limit on the amount of money to be spent on artist hospitality, which could include backstage food / drinks, hot meals, towels, dressing rooms and furniture, and anything else that isn’t production related. It’s recommended to go through the artist’s hospitality rider and see what they’re asking for, and then set your cap that results in a reasonable compromise.

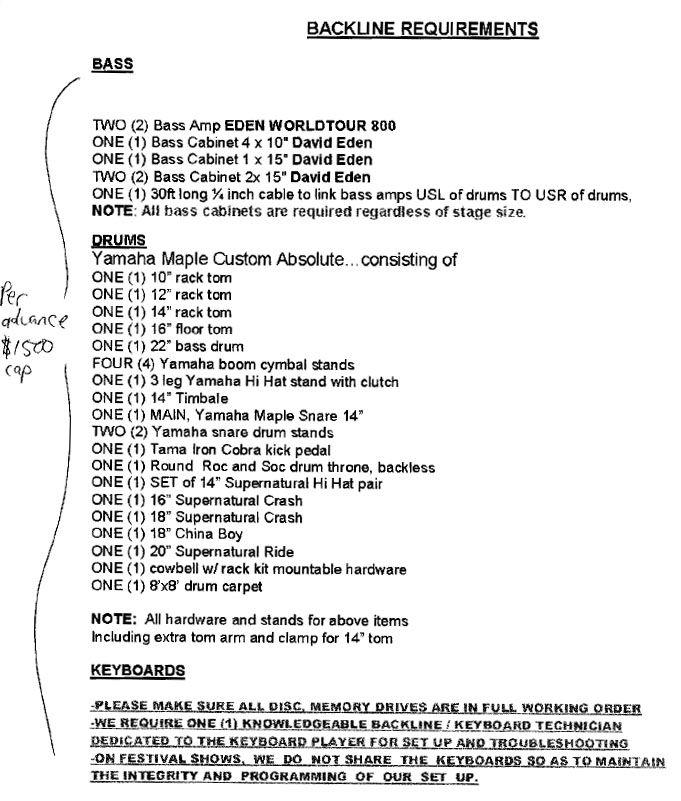

- Backline Cap – this is a limit on the amount of backline the band can request. See what they’re asking for – if anything – in their technical rider. You may want to get a few quotes and see what it may cost you, and set a cap at a number you’re comfortable with. This way they will need to pay for anything above and beyond what was originally agreed to. On occasion, bands will try to negotiate a backline buyout and handle it themselves; this can also work well in some cases.

- Ground Transportation Cap – if the artist is flying in for the performance (also known as a “fly date”) then they will often need transportation to/from the airport, the hotel, and the venue. Some bands will handle it on their own but many will ask for ground transportation. See what’s in their rider and if it’s feasible for you to handle; if not, state what you will and won’t provide and up to what cost.

- Hotels Cap – artists and their hotel accommodation requests can vary wildly, so you’ll want to be sure you have a good understanding of how many and what type of rooms they will need. You’ll want to either have the artist handle this internally (you’ll “pay” for it as part of your guarantee) or if they need you to handle, you’ll want to set a cap – this is one item that can easily get out of hand, since hotel rates can vary and artists will sometimes want to add or change rooms.

- Production List – you will want to show them what sort of stage / sound / lighting package will be provided, and have them agree to it at the contracting phase, rather than after contracts are signed, especially if their technical rider states a PA system, lighting rig, and/or stage size that doesn’t match with what you’re providing. Most artists are able to play on almost any reasonable production setup, but they need to know ahead of time what you’re providing so there are no surprises. They will work with you on any true red flags they discover here before contracts are signed.

- Merchandise Split – a decent revenue stream – especially for merchandise heavy bands including Christian Rock bands – is income from merchandise sales. The standard split is 80 Artist / 20 Promoter if the artist sells, or 75 Artist / 25 Promoter if the venue sells, with media being 90 Artist / 10 Promoter. If you are selling, you’ll want to hire a reputable person or company – based on the amount of the merchandise being sold that understands how to count in inventory, take sales via cash, credit card, and/or other payment options, and count inventory back out with the artist(s) at the end of the night for an accurate settlement. Sometimes it’s just easier to let the artist sell and you settle with them on merch when it’s time to give them their payment for their performance – the smaller the event, the better off you are having them sell. But larger events, with multiple acts, it makes more sense to have someone selling on your behalf.

- Payment terms – something you’ll want to determine with your event and festival executive team beforehand is how you would like to structure payment. Many larger special events and festival contracts offer a flat rate guarantee that doesn’t change regardless of how many tickets are sold, but often smaller events, club shows, and festivals may try and add in a backend deal, whereby the artist will receive a percentage of the profits after the break even point has been reached. This can help reduce the guarantee price and compel the artist to heavily promote their performance, since their compensation is tied to attendance. Common break even percentages are 85% Artist / 15% Promoter.

- Compensation terms – your standard artist contract will ask for 50% upon receipt of a fully executed contract or 30 days prior to the performance. Depending on the situation, the agency may ask for more than this, but it’s rare. If you’re a first time talent buyer and it’s a high risk act (financially), they may want to see more money upfront. And other times, after a relationship has been established, you may see the deposit be down to as little as 10%. Often this will be in the form of a bank wire (but cashier’s checks are normally accepted as well).

Day of show, you’ll want to have cashier’s checks ready as well as any cash advances the artist may ask for (often they do this to pay their caterer, crew, or other petty cash day of show expenses). If they request a wire, make sure it’s in the contract that it will be sent the next business day following the performance; if they play on a Friday night, they won’t see that wire hit until next Monday at the earliest.

Reviewing and Marking Up the Artist ContractSo you’ve made your first offer (which should almost always be to the headliner(s) as they’re the most important and often hardest to get) and they have accepted! This is a great step forward, but now the details of the contract need to be hashed out. You will want to receive their complete rider as well as all legal verbiage from the agency and review it thoroughly. At this point, you will want to “redline” the contract where specific elements either don’t apply or you think shouldn’t apply. But what would those be?

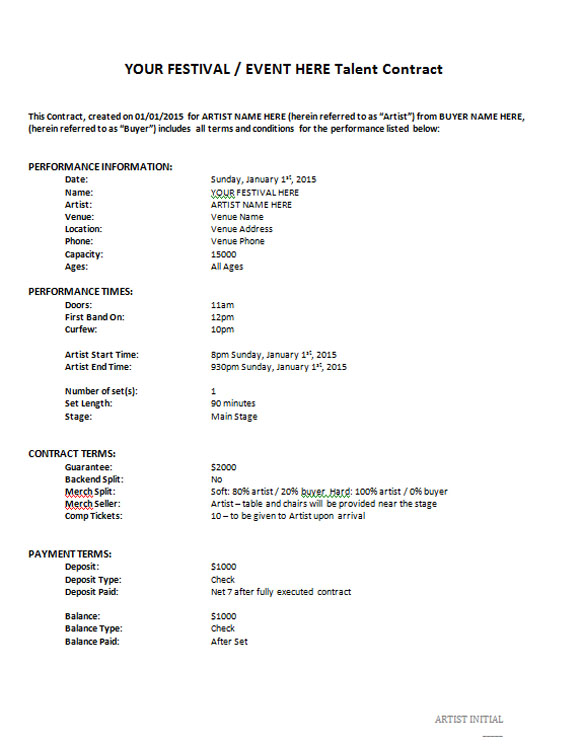

Below is a screenshot of a typical boilerplate contract – note, however, that this is a very simple contract and ones from the major booking agencies will be much more detailed. Every contact will include information on the ARTIST, the BUYER (or PURCHASER), the AGENT, and sometimes the PRODUCER. Usually the Contract Face (or the first page) will show the most important details summarized, including payment terms and conditions, along with signatures for the BUYER and the AGENCY (or ARTIST).

Download this as a Word Document

As you read through the contract, you’ll want to focus on these points – many the same from your offer form – and make sure they align with what you initially offered and/or are something you’re comfortable signing off on:- Radius Clause

- Hospitality Cap

- Backline Cap

- Ground Cap

- Hotels Cap

- Production Gear List

- Force Majeure – a Latin term meaning “superior force”, this is often seen in contracts to cover “acts of God” or unforeseen / uncontrollable events that prevent the artist from playing. Examples include acts of war, riots, strikes, earthquakes, or epidemics. In these instances, neither party would be liable for performance (artist) or payment (buyer). Often if this happens the two parties will come to an understanding about a future performance and/or compensation, depending on the situation.

- Weather Clause – if, for example, an artist is ready to play an outdoor festival set but severe weather causes the event to be evacuated, because the band was ready and willing to play, this clause would ensure they would receive full payment. (The event is expected to recoup their costs with their rain insurance policy). Where possible, you want to have this be a MUTUAL agreement between the parties, not one that the artist decides.

- Cancellation Clause – often bands will want to insert clauses that allow them to cancel for any reason, forfeiting any deposits and waiving any future payments due, up to 30 days prior to the event. When possible, it’s best to get this struck or pushed at least 90 days out, especially for headliners. Having a headliner suddenly cancel a month out would put the festival organizers in a precarious position to try and find a suitable replacement at the same compensation level. If the artist cannot move forward without a 30 day cancellation clause, you will want to try and negotiate to include payment of “out of pocket” expenses associated with their cancellation, including any marketing / advertising you have done up to that point.

- How they need to promote it – be it through social media channels (and using the proper hashtags), on their website, and/or participating in pre-show interviews.

- Meet & Greets – do you need to require one with them for contest winners, VIPs, sponsors, etc? This is the place to lock in the details on how many people allowed to meet & greet the artist, where this will take place, and at what time (before the performance or after the performance).

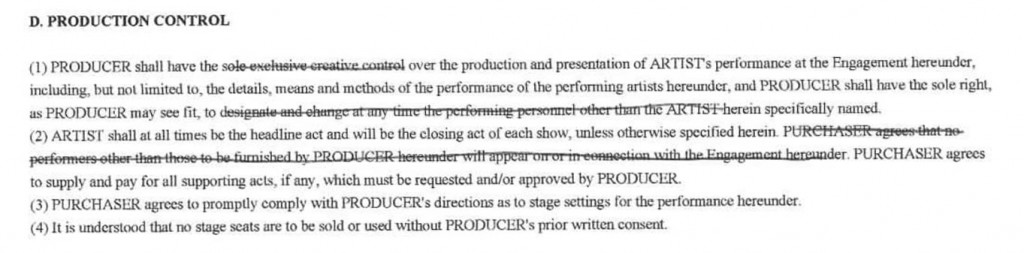

- Any restrictions on having “total control” of production from load-in to load-out – most festivals will redline this out as it’s meant more for concerts where the artist is the sole or headlining act. The Promoter needs to have final say on production elements, when to open doors, and so on. Below is an example of a partially lined out clause about production control (click on image to view a larger version).

- Any restrictions on sponsorship signage or engagement – you will want to make sure you protect your ability to display any banners / signage that have your sponsors and/or the venue listed. Some artists are very particular about how branded the stage area is.

- Where arbitration / mediation would be held if there is a legal dispute – if you ever had a legal dispute with the artist or agency, ideally you would like any mediation or arbitration hearings to be in your state to minimize your travel and related expenses.

- Insurance requests – if the artist is requiring to be listed as additional insurance on your company GLI policy, you will also need to require them to list your company as AI on their policy, which should be, at a minimum, $1 million per individual occurrence.

- Ability to record and/or broadcast the performance – if you wish to stream and/or sell the performance you’ll want to work out the terms here; by default most artist contracts will include verbiage forbidding any audio or video reproduction of their work.

- Any cash advances they need

- Payment terms

- Compensation terms

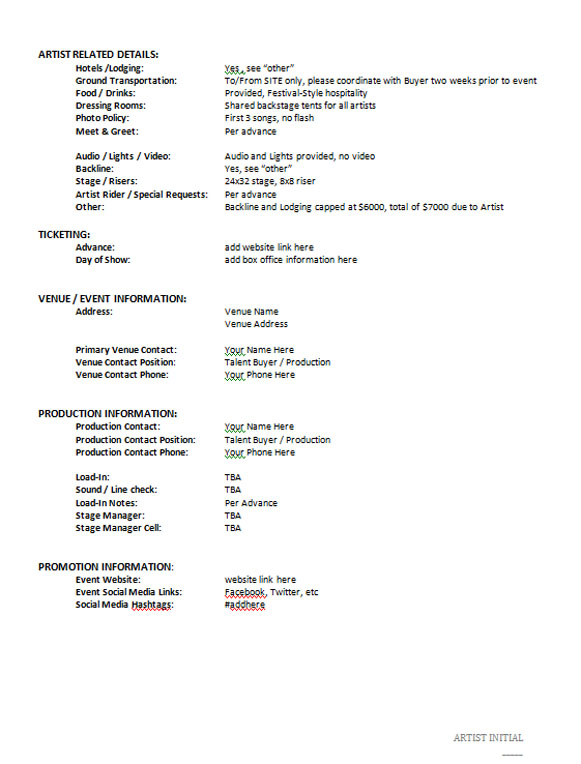

As you work your way through the contract and rider, sometimes the best way to mark up various points is to write “Per Advance” on them. This means that you are agreeing to honor some, but not necessarily all, of the points therein once it has been properly advanced with the artist representative (often the Tour Manager for hospitality / transpo / hotel needs and the Production Manager for production / backline needs). It’s even better to also include a cap, as listed above, so you aren’t running the risk of them demanding everything when you thought they wouldn’t, putting you over budget.

One important point – you don’t want to just write or stamp “Per Advance” throughout the entire contract / rider as there are several key points, especially those listed above, that are in your best interest to clarify prior to contracting.

Below is an example of a marked up hospitality rider with “per advance” and the hospitality cap listed:

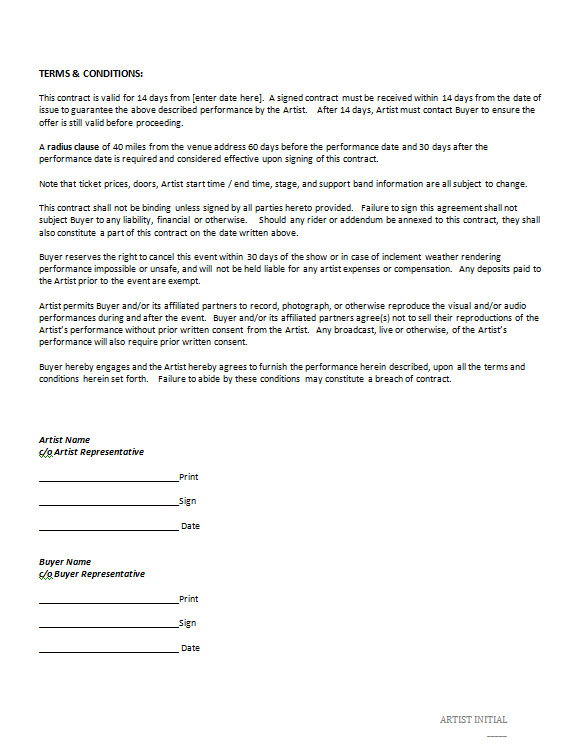

Below is an example of a marked up technical rider showing “per advance” with a cap for an artist’s backline needs:

Receiving a Fully Executed ContractBefore you send off the signed contract for the agency to review and countersign, you may want to have your legal counsel review it just to make sure you didn’t miss anything that could hurt you down the road. If you don’t have / can’t afford legal counsel, make sure you clearly understand everything you are agreeing to and what the worse case scenario would be for you financially or otherwise.

As a side note: never sign anything you may not be able to deliver on or live up to. And never assume or rely on the hope that ticket sales will pay for all of your expenses – you will need to be able to cover all of your costs regardless of how well your event or festival does. Otherwise, the financial and legal ramifications from a breach of contract could be significant and do irreparable harm to you and your business.

Finally – you have made it through the research and development stage; you’ve created your dream lineup; you’ve made formal offers; and you’ve signed your properly marked up contracts. You’re almost there – the next important milestone is when you receive a fully executed artist contract back from their agency. Once that happens, you may – in theory, at least – sit back, relax, and let the accounting, production, marketing, and site operations teams take it from there. Just make sure they have everything they need to properly handle the deposits, production needs, hospitality needs, and day of show compensation to ensure a smoothly run experience for all. - Researching artists that may fit your budget and your event or festival’s entertainment goals